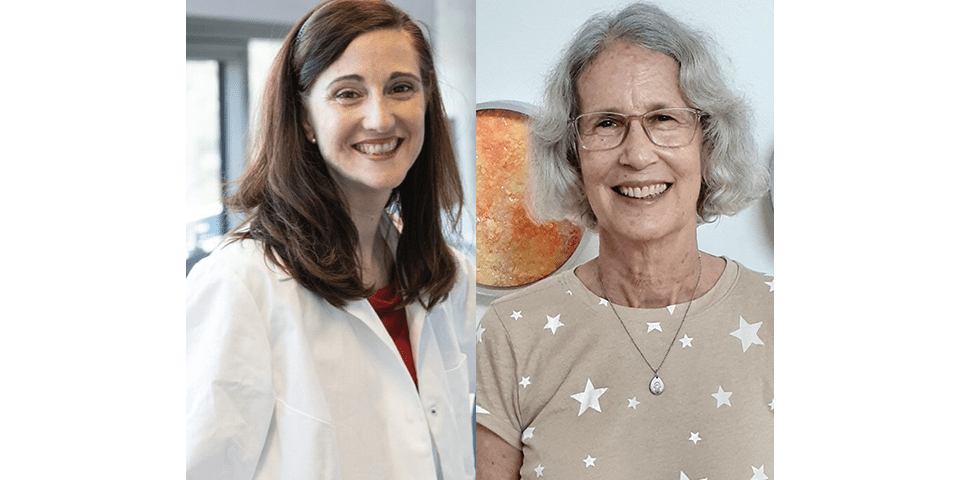

In honor of International Women’s Day on the 8th March, and World Organoid Research Day on 22nd March, we have been privileged to interview two extraordinary women about their experiences working in science: Dr Hynda Kleinman, one of the co-inventors of Matrigel, and Dr Meritxell Huch, of one the Directors at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG).

Dr. Kleinman has published over 440 papers and been awarded 10 patents, 3 of which have been successfully commercialized. Matrigel is used worldwide and was among the top 15 NIH patents bearing royalties for many years. She has received numerous national/international awards for her scientific accomplishments.

For her pioneering work on developing organoid models, Dr Huch has published over 70 papers and been awarded 5 patents, 4 of which on organoid technology which have been successfully licensed and brought royalties to the Dutch academy of sciences. She has received several awards, including the Hamdan Award for Medical excellence, the Women in Cell Science Prize from the British Society, the EMBO Young Investigator Award, and the BINDER Prize.